Not long ago, during a discussion with a Zoomer colleague about how to find research material, I realized that he had never experienced internet search back when it was good. I tried to explain how it used to be easier to find information from good-faith experts, but I don’t think I really got the point across. Let me try again.

Nowadays we take it for granted that any time you run an internet search, most of what you find will be Out To Get You. It’s content marketing cobbled together by chatbots, or by people who might as well be chatbots. It’s algorithmically optimized to squat in the top search results as part of someone’s marketing funnel. It’s propaganda by NGO hacks, or recent news articles on a different topic that shares a keyword, or literal paid advertisements, or something. Maybe it has a little bit of information about what you actually wanted, and maybe it’s a trailhead towards a deep and serious source, but you don’t expect to just… find what you’re looking for, presented straightforwardly.

(I know the title promised this would be about academic research. Bear with me, I’m getting there.)

My younger readers may not believe me, but internet search wasn’t always like this. Back in 1999, few people had figured out how to take advantage of search engines that way. When you looked for information about how to tell if your bread is rising correctly, or about South Korean cement manufacturing, or the musical influences on Igor Stravinsky, or whatever weird thing, Google would pull up high-quality reference material, or blogs and BBS arguments among disagreeable weirdos who specialized in the subject and usually knew what they were talking about. The tricky part wasn’t sifting through a mound of spam and paywalls and halfassed summaries to find something legitimate; the challenge was making sense of a high-context insider discussion on a topic you were trying to wrap your head around.

As we now know, this didn’t last forever. A cottage industry arose of finding some search term and churning out low-cost copy on the subject in order to serve ads to people trying to find real information. Specialists in “search engine optimization” popularized their techniques as consultants to big companies, and before long this became standard practice. In their efforts to keep these problems from getting totally out of hand, Google and other search engines weighted search results towards a whitelist of standard lowest-common-denominator websites. The long tail of the internet could no longer be found from a simple search.

The hyperfocused specialists and weird nerds are still out there thinking and writing about their special interests, of course, but it’s much harder to find. You have to trace back sources and citations, or sift through the Twitter feed of a relatively knowledgeable author who mostly likes to yell about elections, or dig up the Youtube video with 86 views by a Turkish grandfather who just shows you how to replace the damn part, or you need to know a guy whose roommate is part of the right group chat. Maybe it’s out there, but you can’t just find it with a search.

Worse, the weirdo specialists have a harder time finding each other. The days are gone when the people who are really interested in South Korean cement manufacturing could just Google the mailing list and start talking with each other. Instead they’re wandering through a desert of paid industry reports and Bloomberg articles. Productive discourse has retreated to walled gardens, and as a consequence there is much less of it.

What does this have to do with academic work? Well, again, whenever you find an academic publication, you can’t just assume it’s probably in good faith. You have to start from the assumption that it’s Out To Get You, because nine times out of ten, it is. Maybe it’s activist bullshit based around tendentiously redefining words, or maybe it’s built on fabricated medical data, or maybe it’s some kind of statistical jiggery-pokery to pull statistical significance out of unreplicable noise, or maybe it’s just a watered-down summary of better work, or maybe the author stapled together plagiarized excerpts of other papers which she didn’t understand—sorry, the author merely omitted quotation marks and citations. Or maybe it’s one of a hundred other things.

And again, this might be hard to believe if you haven’t read much academic work from before 1990 or so, but it wasn’t always this way. Sure, it was never perfect, and you always have to read everything with skepticism. But the average quality was much better. Other people have written more deeply than I ever will about the forces that make today’s academic work so shoddy, about p-hacking and publish-or-perish and ideological fads and all that. What I know for sure is that when I read academic work published in 2014, I’m pretty likely roll my eyes and mutter about how no serious person would even bother with this crap and set it aside, whereas when I read something from 1964 then it’s much more likely to be, at the very least, a good-faith effort by a reasonably bright person saying something they care about.

For example, lately I’ve been researching the economic history of medieval China. I find that almost everything that’s actually worth reading was written between about 1940 and 1990. Before that, there wasn’t much English-language research that was based on a deep understanding of Chinese records. After that… I dunno, man. The recent stuff I’ve found is mostly shallow crap churned out to pad publication counts. The best recent work is summaries and retreads of older giants like Mark Elvin and Chi Ch'ao-ting and Joseph Needham—and these retreads contain real knowledge, but it adds very little to what came before, which is kind of embarrassing considering much of the midcentury stuff is absolutely terrible at big-picture theorizing even when their local scholarship is extremely good. (This is only partly because many of that generation of China scholars were Maoists.)

The world is a big place, and I bet that somewhere out there, someone today is writing excellent work about Song dynasty merchant families which I would dearly love to read, but I haven’t been able to find it among the sea of bullshit and retreads. I’m mostly sticking to older work while I wait for the robots to get good enough at translation that I can read Chinese-language scholarship and primary sources.

Field after field is like this. A hundred years ago, all the important physicists knew each other and were in constant dialogue. During the most rapid advance of theoretical physics in the history of the human species, it was possible to, basically, take a group photo of the entire field:

The 29 participants in the fifth Solvay Conference in 1927. Those pictured include Bohr, de Broglie, Curie, Dirac, Einstein, Heisenberg, Lorentz, Pauli, Planck, and Schrodinger. The only first-rate legendary physicists absent were Rutherford and, if I’m generous, Michelson. Both had attended an earlier Solvay Conference, and Michelson was 75 years old.

Today it would be effectively impossible for a physicist to personally know all the other top physicists. In the U.S., the number of physics PhDs awarded per year grew from under 20 in 1900, to nearly 2,000 by 2018. Imagine trying to get all the leading theorists together for a group photo today.

Physics is the norm, not the exception. From 1900-1999, the U.S.’s production of academic doctorates increased a hundredfold, while its population increased by 3.5 times—that is, almost thirty times more PhDs per capita.

Chart from U.S. Doctorates in the 20th Century, Thurgood, Golladay, & Hill, 2006.

Of course, after this expansion, 21st century physics has not advanced a hundred times faster than it did during the time of Albert Einstein and Neils Bohr. We do not have thirty times more Einsteins and Bohrs per capita. A doctorate just means much less, now, than it did. The fraction of physicists who can generate genuine new knowledge and insight is fairly small. Most of today’s physicists would not measure up to the standards that the field held for itself when that photo was taken in 1927. To their credit, physicists have maintained intellectual and educational standards better than perhaps any other academic field. Medicine is in notably worse shape, for example. And outside of the hard sciences, well. It isn’t good.

The dilution of the top experts doesn’t only mean that it’s harder for you and me and the New York Times to tell the first-rate researchers apart from the sea of mediocrities. It’s also harder for those on the cutting edge to find each other. The real ones can tell, when they look deeply at each other’s work, but that takes a ton of time and effort, so it’s not always practical. When an important new theory is published, instead of being circulated and torn apart by the two dozen people whose opinions matter, it’s sent off to some nameless apparatchik for the hollow bureaucratic ritual of peer review, so that the reviewer can demand bogus citations for himself and his friends. Every field has some real scientists doing excellent work. But twenty-nine thirtieths of their peers are cargo cultists, outright fraudsters, or at best just aren’t all that great at their jobs. Much has been made of “impostor syndrome” in academic research. The fundamental cause is that there aren’t enough non-impostors to fill all the positions.

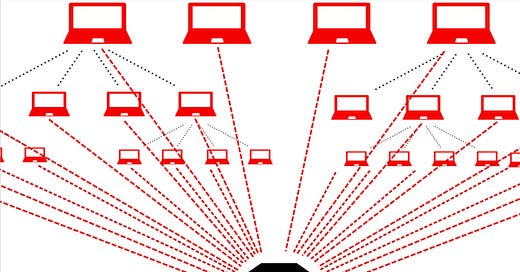

The effect is similar to a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack. This is when an attacker shuts down an internet server by sending a massive flood of bogus communication requests, overloading the machine’s bandwidth until it is unable to respond to legitimate requests. Academia’s minority of serious researchers are also flooded with a massive, hostile flood of bogus communication requests. If most of their ostensible peers can’t discover new knowledge, then how will they find peers to work with? If most publications aren’t worth the time it takes to read, then who will bother to read the minority that are actually good?

Intellectual progress is held back substantially by these problems. If the academics do not raise their standards—and it seems like the opposite is more likely—then over time the real work will move gradually, and then suddenly, into different channels that are able to filter out the noise. This process is already underway. Because the internet commentariat’s intellectual elite is more attentive to an argument’s substance than whether it observes the bureaucratic forms, these circles are much less vulnerable to getting DDoSed by floods of well-formatted bullshit, and are slowly picking up more and more of the jobs that academia is abdicating. The 21st century’s most influential philosopher, so far, is an uncredentialed blogger and fanfiction author who lacks even a high school diploma. When it comes to understanding of how society works, academia still has a lock on the lowest common denominator, but a growing fraction of the intellectual elite are leaving behind the institutions for internet self-publishing. Even archaeology is seeing some efforts to work outside of the academy, with well-funded projects like the “Vesuvius Challenge” to decipher the Herculaneum Papyri. Whether the universities can reverse course, and if not then how long it will take before they are simply left behind, remains to be seen.

With physics (speaking as someone in the field) I'd argue something else is going on. After table-top experiments and university-scale research programs were exhausted, physics has had to rely on larger and ever more specialized technology to learn one useful thing about the universe. Compare the rutherford scattering experiment to the LHC! So we really do need hordes of PhDs, engineers, and technicians to do anything and we actually still do not have enough people! The number of people that can do what Einstein did - path integrals and tensor algebra - is enormous but the next generation of mathematics must use that as a starting point for a decade of mathematical specialization.

Still academia has similar challenges with the new reality of physics research. What happens when the length of time to build the experiment is longer than the PhD? What happens when an experiment needs decades of experience in a minor technique and then that technique becomes obsolete? What happens when the science machine becomes so complicated that scientists end doing empirical analysis much like an economist or epidemiologist would? What happens is that academia publishes papers and funds grants that would not pass muster in yesteryears even when the amount of effort and competition that goes into them far exceeds traditional expectations.

Who is the 21st century’s most influential philosopher, so far?